Winemakers use artificial intelligence for sales intel

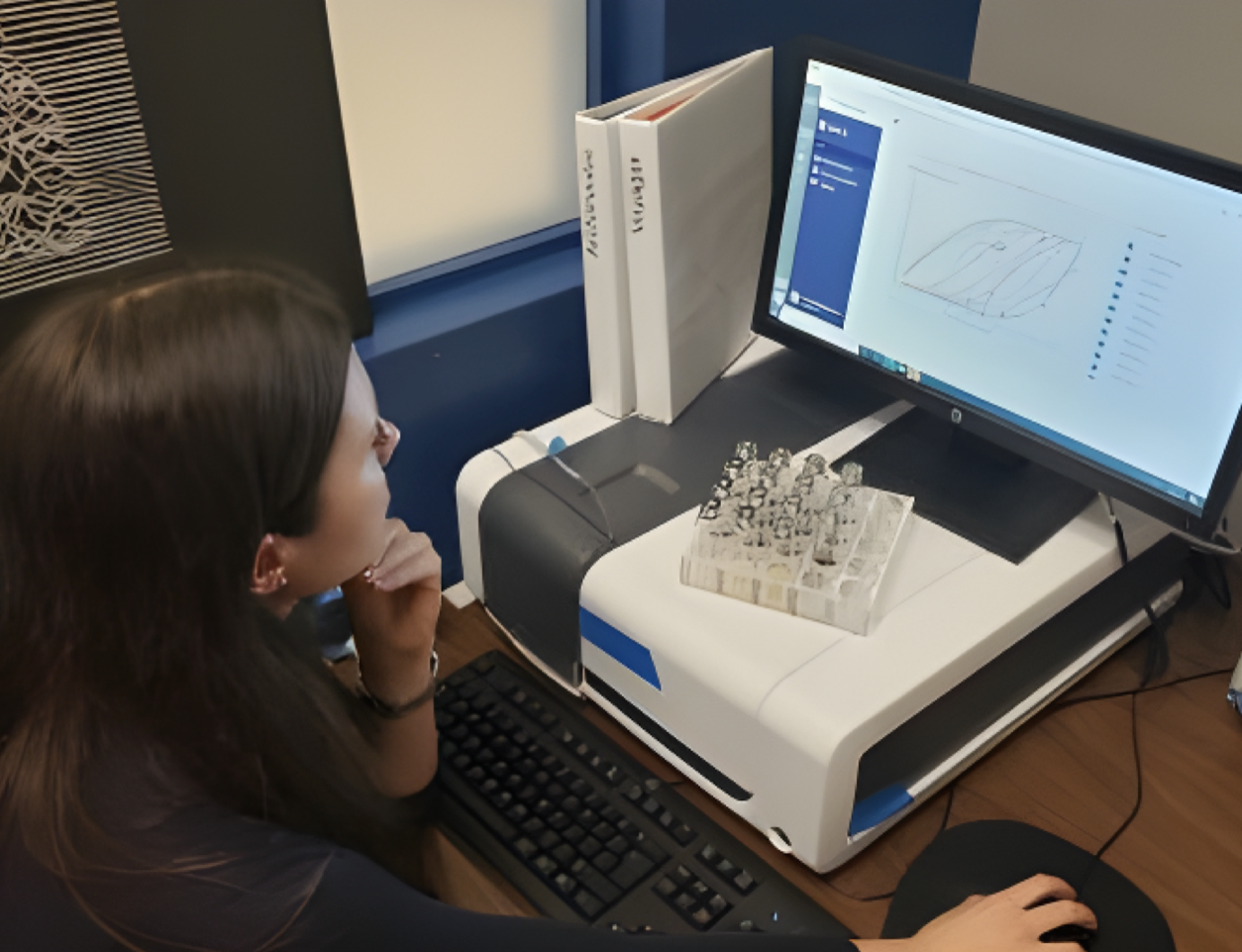

Katerina Axelsson, CEO and founder of San Luis Obispo-based Tastry, uses artificial intelligence software to guide winemakers in their craft. Through chemistry, machine learning and AI, the company tests wines and can identify compounds that are out of balance. Once identified by the lab, a winemaker can correct any imperfections during a second fermentation.

Photo/Courtesy of Tastry

By Rob McCarthy

A Central Coast laboratory that taught a computer to taste wine is making artificial intelligence less mysterious—and more accessible—to winemakers and their sales teams.

The Tastry lab team relies on AI to check the ratios of compounds in wines their clients send in from California to Australia, according to Charles Slocum, the chief business officer of the San Luis Obispo-based wine lab. Slight imbalances can show up in the flavor, texture and alcohol content of a wine.

The AI assistant compares a wine sample against the data on file and makes recommendations to the winemaker, winery or broker about any ratios that are out of balance or discrepancies, including sugar or alcohol content, Tastry officials said.

AI scans the profile of a wine from a client and compares it against data collected about a similar wine, based on what the winemaker and vineyard owner are hoping to match, Tastry’s founder and CEO, Katerina Axelsson, said.

“You’re sitting down trying to figure out how similar the profiles are. We can do that in 48 hours,” she said. “We say the objective for the AI is to match the flavor and sensory profile of this prior vintage.”

Because the wine analyzer doesn’t have a palate, it compares the percentages of sugar, acid, alcohol and other compounds that are mashed together to produce wine. AI looks for ratios that are too high or too low and can scan for a million different combinations, which would take years for one person to do.

Because the lab analyzes thousands of bottles a year, the computer is always learning about wine and quality issues. Technologists use the term “machine learning” to explain and demystify the AI process.

Nitin Nitin, a professor of agricultural engineering and biology at the University of California, Davis, tracks AI and innovation in food production. He’s heard of food companies using AI to perfect flavor or boost protein content in their recipes, but the work of Axelsson and her lab is altogether new.

“I understand the concept, but I can’t say I know of many companies that are doing this,” Nitin said.

He agreed that because of the chemical complexity of wines and the nuances that makers hope to get, it would be easy for a chemist or lab technician to miss something in the final report.

“Especially in those situations, humans may not be able to see the big picture, but AI could,” Nitin said.

Collecting the data to build an AI-assistive system like Tastry’s took years, and Axelsson, who is a chemist, worked in other wine labs and saw a need for data-driven decision-making by wineries rather than relying on just past experience and subjective opinions about the quality and marketability of Central Coast wines.

Axelsson’s team of 26 employees also crunches data collected from 200,000 people about their palates to predict what consumers in specific regions of the country will buy and drink, according to Tastry. AI, in one instance, asked people if they like onions, and then used the responses to answer the question on the winemaker’s mind: Will this product sell out, and at what price per bottle?

The questionnaire used to build the database about Americans’ palates has 150 questions, Slocum said. AI used the information about likes and dislikes—including responses on black licorice and onions—to point winemakers and retailers in the direction of the right markets for them.

AI is a promising new tool for vintners because, unlike humans, the technology doesn’t experience “palate fatigue” or get confused about what’s in the glass, winemaker Cameron Hughes said.

His San Francisco-based company, Cameron Hughes Wines, specializes in acquiring, re-blending and marketing fine wines under his eponymous label. The number of blend components present in tanks being reused in a commercial operation is overwhelming, he said in the May podcast “My Ag Life.”

“It’s a risky proposition from an inventory standpoint. This is where AI can help you and suggest particular blends to you, and you can decide which one you want to do,” Hughes said.

Tastry’s recommendation avoids what Hughes calls “palate fatigue” and reduces the risk of guessing wrong about what consumers want, he said. A data-assisted method of making wines and correctly marketing them is a huge time-saver for a winemaker, he said, but it doesn’t replace the winemaker.

“Winemakers are still going to be needed. This is just a tool to help them on the blending side,” Hughes said.

AI is cropping up in vineyards for other purposes, too. Gamble Family Vineyards in Napa Valley mounts cameras on tractors and sensors that collect real-time data, which guide farming decisions and yield estimates. This emerging technology has a host of potential applications in California farming, Nitin of UC Davis said.

It could be integrated into seed and plant breeding to boost nutrient content or achieve better color or taste, he said. As some crops move indoors, AI could help farmers adapt their production methods and pest or disease control programs for the indoors.

Growers use their experience to plan, harvest and predict yields, and information technology won’t replace that, Nitin said. Still, there are opportunities with AI for growers to fine-tune their operations.

AI makes recommendations, as with any adviser or consultant. What growers do with the advice is up to them.

“It points them in a direction,” Nitin said.

(Rob McCarthy is a reporter in Ventura County. He may be contacted at robmccarthy10@yahoo.com.)